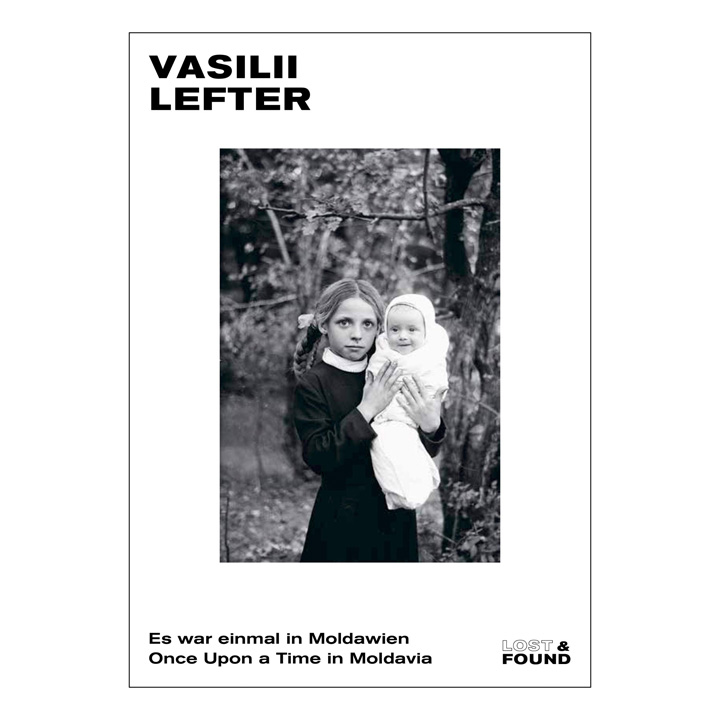

Vasilii Lefter

Once upon a time in Moldavia

€ 12.00

incl. VAT plus shipping costs

14,8 × 21 cm

48 pages | 49 illus.

German/English

Edited by Beate Kemfert, Markus Hartmann

Graphic Design Antonia Grösschen

Booklet in cellophane bag

available

ISBN 978-3-96070-023-4

Sold out, last copies

Description

lost&found

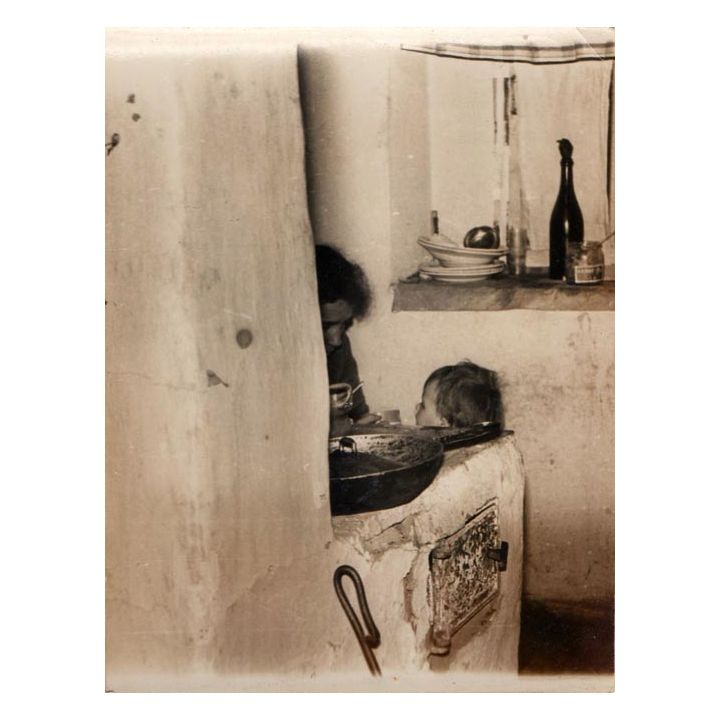

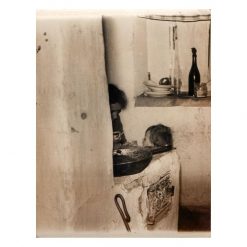

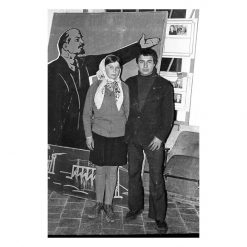

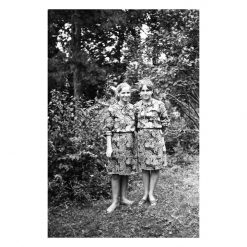

This new photo book(let) series presents analogue photographs and picture archives. Intuition, pure chance, odd encounters, and the slow passage of time helped in discovering the images and archives. All of them have their own remarkable stories: the story of the individual photographer, the story of the photographic subject, the story of each archive and its discovery, and not least the visible story of the unavoidable deterioration of analogue photographs, caused by production, use, and storage. All of the images are reproduced unretouched and thus bear the traces of their history, from the depths of their emulsions to their surfaces.

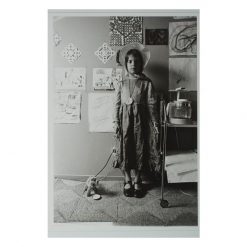

Vasilii Lefter | Once upon a time in Moldavia

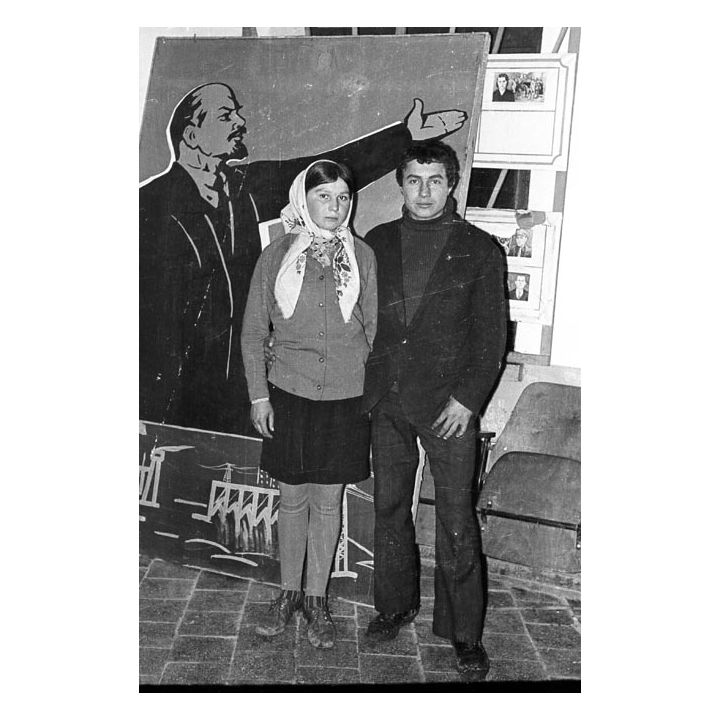

The photographs of Vasilii Lefter (1943–1982) were never published during his lifetime. Yet it was always his dream to be taken seriously as a photographer or artist and to have international exhibitions and publications. When his daughter, the artist Tatiana Fiodorova (born in 1976), discovered them, the boxed images had been gathering dust for twenty- five years on the balcony of her parents’ apartment in Chișinău, the capital of Moldavia. Lefter left behind a Kiev camera and countless small-format photographs, negatives, rolls of film, drawings and paintings, and stencils and drawings for the propaganda posters that he had designed and painted as a freelance graphic designer—a position that could not really exist in the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic—for the kolkhozes of the region. He gave up his conformist but unsatisfying desk job at the Ministry of Building, where he had been employed since 1970. Lefter was self-taught, his photographs were black and white, and he developed his small-format pictures in his bathroom at home. He spent a large portion of his meager earnings on his passion for photography. He often spent weekends in the countryside around Chișinău, where he photographed the villagers in their gardens, at weddings, in the forest, or in community rooms. Family members posed for his camera, often as couples. Babies and status symbols such as portable radios, which often reappear in his pictures, were often shared by the sitters as props. The often identical clothing bears witness to the uniformity of Communist fashion. Now, thirty-six years after his death and twenty-eight years after the fall of the Iron Curtain, the photographs are being shown for the first time in an international exhibition—the fulfilment of his dream.